Disease Treatment Using BCI Technology

Tiffany Jong, Yan Luo, Ayush Agarwal, Robbie Ingram, Kavya Sood, Veeresh Neralagi

Introduction

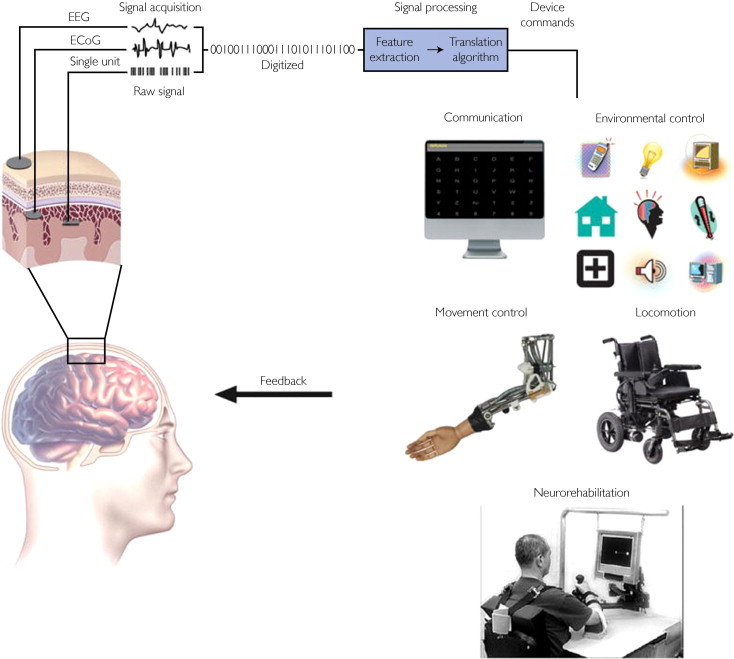

Brain Computer Interfaces (BCIs) allow us to record and interpret signals from the brain, enabling us to explore new treatment methods for neurological diseases. BCIs are able to assist with treatments such as rehabilitating the motor functions of paralyzed patients, improving/recovering sensory processing abilities, and improving the rehabilitation of sensorimotor function after a stroke (1). However, different treatment methods will utilize different types of BCIs. When developing treatments for diseases, it’s important to first differentiate between the two main types of BCIs: invasive and non-invasive.

Invasive methods commonly involve implanting the BCI directly into the cortex to measure the activity of populations of neurons (2). While invasive methods produce the highest quality signals, they also have the highest risk of damaging the brain. One drawback of invasive BCIs is that they commonly lead to the formation of scar tissue around the electrode, which can disrupt the signal (2). Due to the high risk associated with invasive BCIs, their use is mainly limited to patients suffering from blindness or paralysis.

There are five main types of non-invasive recording methods: magnetoencephalography (MEG), positron emission tomography (PET), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), and electroencephalography (EEG). Of these five recording methods, EEG is perhaps the most commonly used method due to its low cost and portable hardware.

Because of its lower cost and increased portability, EEG presents a unique opportunity to treat motor, cognitive, emotional, and perceptual disorders. Treatment for these disorders rely on neurofeedback, which is the use of electrical signals from the brain to train itself and self-regulate its own improvement (3). Neurofeedback isn’t necessarily a cure, but rather a self-correcting system for the brain to use when modifying existing circuits or patterns of connectivity.

In the following sections, we will discuss some ways in which BCIs can be used to treat different diseases and disorders. We will begin with a discussion on BCIs in the treatment of substance abuse, followed by a section on BCIs as they relate to Alzheimer’s disease. In the next discussion regarding BCIs and paralysis, we will go over recent research efforts to aid patients through non-invasive techniques such as EEG. Afterwards, we will offer our perspective on the future of BCI technology and discuss other ways in which these tools can be used to improve the lives of patients.

Substance Abuse

Our brain is not always under our conscious control; consider how difficult it can be to control a dream while sleeping, stay focused while studying, or even fall asleep in the first place.

Additionally, many drugs can make cognitive processes seem as if they are out of your control. Individuals suffering from drug addiction often find it difficult to avoid thinking about drugs or drug-related environments, and they often don’t know how to stop thinking about them once those thoughts occur. What if there was someone who could watch the activity of your brain, and warn you if you are beginning to crave cocaine or other drugs? Using EEG technology and machine learning, researchers have successfully developed a hardware system that can help decrease the likelihood of relapse in individuals with substance abuse disorders.

The idea of using BCI technology to help a subject better understand and gain self-control over their brain function is called neurofeedback (as discussed in the introduction). When monitoring brain activity using EEG technology, a grid of small metal discs attached to thin wires (electrodes) is placed on the scalp of the subject. The computer records electric signals resulting from the electrical activity of the brain. The recorded signal is very similar to a sound wave; it is composed of different frequencies, and those frequencies appear with different amplitudes. Although the waveform of the recorded brain activity collected through EEG results from our own cognitive processes, it is tough for human beings to understand in its raw form.

Using computer algorithms, researchers can separate different rhythms from the collected brain waves and then depict them. Two significant rhythms used in neurofeedback that are relevant to those suffering from substance abuse are the beta and the sensorimotor rhythms (SMRs). The beta rhythm is related to feelings of anxiety, intense thinking, and concentration. Bursts of beta waves are correlated with a strengthening of sensory feedback or with actively resisting and suppressing a movement or thought.

SMRs are produced when a sensorimotor region is idle or inactivated. When a sensorimotor area in the brain is active, the associated region will produce a less intense SMR signal. The researchers specifically chose these two rhythms because there are strong discrepancies in their signal strengths when a patient is either craving a drug or suppressing the idea of taking a drug.

More exciting research was conducted in 2003 at UCLA by a team lead by William C. Scott. The experiment involved 121 individuals suffering from substance abuse disorders, and the goal of the work was to prevent them from experiencing a relapse. Throughout the course of the study, subjects had two EEG biofeedback training sessions five days a week for four to five weeks. During the training, the researchers showed the subjects either drug-related or unrelated pictures, sentences, or conversations, and the participants tried to suppress any drug cravings. The computer monitored the beta and sensorimotor rhythms through EEG and assessed the success of the participant’s suppression. The results were impressive, as after 12-weeks, only 28 out of 121 the test group relapsed when compared to 56 in the control group.

Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that significantly decreases the quality of life for affected patients. Symptoms of AD become more severe as the disease progresses, most commonly resulting in dementia (10). Currently, there is no cure for AD, but studies have found methods to decrease the severity of its symptoms either by early diagnosis or improvement of AD patients’ cognitive performance through the use of EEG. Because EEG technology is most commonly utilized for early diagnosis in the context of AD, that is what we will discuss for the majority of this section.

Early diagnosis is of peak importance for slowing down the progression of the disease, as treatment plans can be made before too much irreversible neuronal damage has occurred. Current AD research is primarily focused on identifying AD in patients during the early stages of its progression, and preferably in the preclinical stage (8). This is particularly challenging, as the preclinical stage of AD is when symptoms of dementia are not yet present in a patient (11).

One method currently used to diagnose AD in patients is to administer a series of neuropsychological evaluations. However, this method is not time-efficient and requires licensed professionals to administer the evaluations. Because of this, hospitals wish to utilize a method with an increased degree of automation. Employing a neuroimaging method such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one option, but it is prohibitively expensive. Because of this, clinicians may consider turning to EEG-assisted methods due to their accuracy, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency. In fact, EEGs have been utilized as a tool for AD diagnosis for decades (12).

An EEG headset or cap operates by detecting brain wave patterns (13). Commonly utilized EEG frequency bands are, from lowest to highest frequency: delta (0.1–3 Hz), theta (4–7 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (>30 Hz). Slow frequencies (<10 Hz) are often indicative of slow brain behavior, usually associated with rapid eye movement (REM) or deep sleep[RI1] . Conventionally, the two types of EEG analyses used in the diagnosis of AD are spectral (linear) and nonlinear dynamics analyses. Spectral analysis is the direct observation of EEG bands and their coherence between different regions of the brain, whereas nonlinear dynamics analyses consist of observing the overall complexity of recorded EEG signals (16).

Intensive research has been done on the spectral analysis of EEG recordings in AD diagnosis. Using this technique, multiple studies have found strong correlations between slower EEG measurements and lower cognitive function scores (17) (18) (19) (20). The slowing of the recorded brain waves is due to AD-induced disconnections amongst cortical regions critical for information processing (15) (16). As the disease progresses, an increase in delta and theta activity and a decrease in alpha and beta activity is also observed (21). Additionally, spectral analysis of EEG recordings has been used to detect early stages of dementia and differentiate between AD-related dementia and other types of dementias such as vascular dementia (23), senile depression (22), frontotemporal dementia (24), Parkinson’s disease (25), and Lewy body disease (26).

Taking a different approach from that of linear dynamics, nonlinear dynamics suggests that lower EEG signal complexity is linked to AD. Nonlinear dynamics of EEG recordings also have to be considered alongside linear dynamics given the largely nonlinear nature of neuronal interactions. Nonlinear dynamics analysis is used by observing the D2 value of the EEG reading, which quantifies the independent variables necessary to describe the dynamics (16). A lower D2 value implies a lower complexity in brain electrical activity, and autopsy-confirmed AD patients have been found to have lower D2 values (27). However, there are some limitations of using this method, such as the presence of noise, the lack of sex and age matched negative controls, and a high degree of freedom (28) (29).

Considering the studies previously discussed in this section, it seems reasonable to claim that EEG technologies are valuable and efficient tools for early AD diagnosis when combined with other methods. Currently, EEGs are not reliable enough to use as the sole diagnostic tool for early AD, as AD progresses in a myriad of ways in patients. More longitudinal studies need to be performed to confirm the accuracy of AD diagnosis by spectral analysis, and the promises of nonlinear dynamics analysis are waiting to be unlocked with further refinement of the mathematical models and algorithms.

Paralysis

According to a paper published in 2016, about 5.4 million people in the United States suffer from some form of paralysis, whether it results from a stroke, spinal-cord injury, multiple sclerosis, or some other cause (30). Leveraging recent advances in BCI technology, researchers are currently working to develop techniques that could possibly aid paraplegic patients regain some degree of independence.

Researchers are utilizing non-invasive BCIs that record electrical signals very similar to those used in EEG recordings. Specifically, they have found that SMRs are a possible source of useful neurophysiological information. Groups from New York and Austria have been working with paralyzed patients in order to help them regain control of their body (31). Patients imagine certain body movements, and useful signals can be recorded from the motor cortex. Their research suggests that when a human imagines a hand movement, SMRs are seen in the resulting EEG recordings. To characterize these signals, the researchers used a magnetoencephalography (MEG) BCI (32). This 270-channel MEG device, “…selects the most responsive MEG channels during imagery or actual movements and uses these channels for the learning of self-control of a prosthetic hand affixed to the paralyzed hand” (31) These MEG BCIs can detect the signals coordinating the movement of even the smallest body parts.

In a more recent study from 2018 (32), researchers sampled four participants with traumatic motor complete spinal cord injury using a more invasive BCI technique: epidural stimulation. This training requires a set of 16 electrodes to be placed on certain spinal segments, and the stimulation of these nodes is maintained at a frequency of 2 Hz for the duration of the study (32). Each training session required the epidural stimulator to be turned on while the patient was either on a treadmill or standing/walking on the ground. Of the four participants the researchers evaluated, two of them were able to walk over ground with assistance after using the epidural stimulator (32). The other two participants were able to walk on a treadmill with some assistance, but not over ground. Considering these participants’ motor abilities prior to the intervention, this is a large improvement; without the BCI, these participants were still unable to stand or walk despite intense training.

Overall, there are many BCIs, both invasive and non-invasive, that are being used to help paraplegic patients regain motor control of their paralyzed body parts. In light of these successes, researchers are looking into many additional ways to assist paraplegics through the use of BCIs. Examples include possibly continuing the use of SMRs and epidural stimulation or even using other neurophysiological information from the brain.

Conclusion

With the rapid advancement of BCI technology and corresponding research on BCI-based treatments, the scope of BCI technologies for disease treatment continues to grow. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) states, “At present, there are over 400 groups worldwide engaging in a wide spectrum of research and development programs, using a variety of brain signals, signal features, and analysis and translational algorithms [2]” (33).

Throughout this article, we have discussed the successful development and use of BCI technologies to treat substance abuse, Alzheimer’s Disease, and paralysis. With these advancements in mind, one might ask: what is currently being developed? What is the future of BCI technology in medicine?

As mentioned above, there are currently a myriad of ongoing research studies and clinical trials. One specific trial that will be completed in 2021 concerns the use of deep-brain stimulation for morbid obesity. Morbid obesity is a disorder in which an individual has an extremely high body mass index and experiences difficulty with basic functions such as breathing and walking (34). This leads to other health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. In this interventional clinical trial, patients will be treated through the electrical stimulation of deep brain structures by surgically implanted electrodes (35). The electrodes will, “… target two brain areas involved in the pathophysiology of obesity” (35).

Another area of growth lies within the realm of mental disorders. Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder that affects an individual’s cognitive function by causing them to abnormally interpret reality (38). Currently, the use of quantitative EEG (QEEG; frequency analysis) when it comes to schizophrenia has been unsuccessful. An article published in the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association states, “The research literature on the use of QEEG as a method to help diagnose depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia is unfortunately dominated by small-scale studies without blinded evaluation, and even in large-scale review papers there has been no attempt to assess the quality of the method” (36). The NCBI further states that the, “…methodology for correlating EEG features and the schizophrenia condition needs improvement to attain more accurate results (39)”. The article also mentions that a, “… machine learning model will assist in this process and replace traditional diagnosis procedures in the future (39)”.

The discussion throughout this article suggests that BCI technologies possess the remarkable potential to treat many diseases, and to improve the quality of life for those who suffer from these diseases on a daily basis. At one point in time, the idea of using BCI technology for disease treatment was a mere fantasy. Today, it is a reality.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5843196/#R1

- http://learn.neurotechedu.com/introtobci/#invasive

- https://www.eeginfo.com/what-is-neurofeedback.jsp

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006322302013628

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19082646

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16161729

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19082646

- https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijad/2014/349249/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197458009001183

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350447

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5619057/

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6090951/references#references

- https://leighbrainandspine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/the-effectiveness-of-neurofeedback-on-cognitive-functioning.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S138824570400015X

- https://www.helpguide.org/harvard/recognizing-and-diagnosing-alzheimers.htm

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S138824570400015X#BIB96

- https://www.karger.com/Article/PDF/106706?casa_token=WMeN7c7KsocAAAAA:gQpQNc1_RxjSEUTLDEIQqmJy078w72FZXNynCHNZKOKSvS5jfh1p8j9-EInMg9yAzFeU3XU2EQ

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0197458094901473

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/article-abstract/774154

- https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-27842-001

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/001346948591048X

- cglink.me/c587864917143444

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178110002465

- https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/67973

- https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/106690

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0987705310000845

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0006322394900043

- http://csc.ucdavis.edu/~cmg/papers/EoMfaDS.ComplexSystems1987.pdf

- https://www.degruyter.com/view/j/zna.1987.42.issue-8/zna-1987-0805/zna-1987-0805.xml

- https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303270

- https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125633

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1803588

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16792275 as cited in https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862632/

- https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/highland/bariatric-surgery-center/questions/morbid-obesity.aspx

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03650309

- https://tidsskriftet.no/en/2013/06/eeg-useful-test-adult-psychiatry

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3497935/

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/schizophrenia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354443

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4383331/